Sponsored by the Friends of Netarts Bay Watershed, Estuary, Beach and Sea (WEBS)

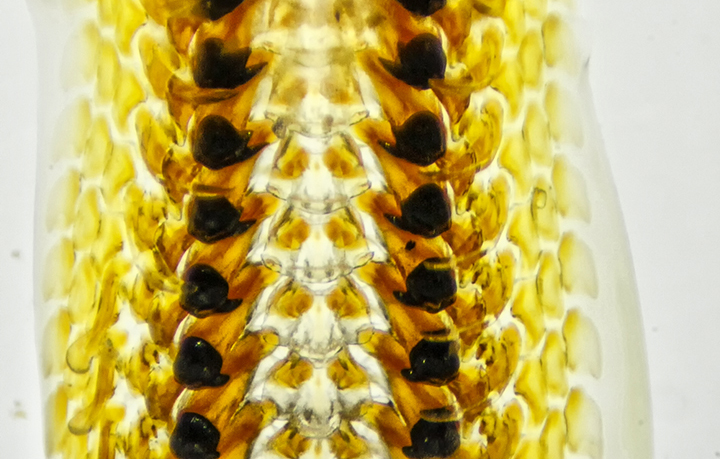

Clinocardium nuttallii

Nuttall's Cockle

Alaska to California

Family Cardiidae

Native

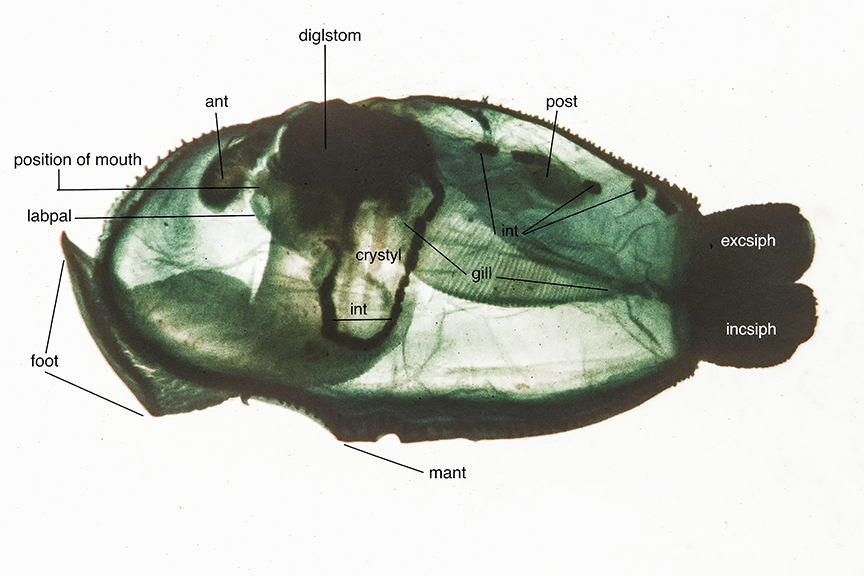

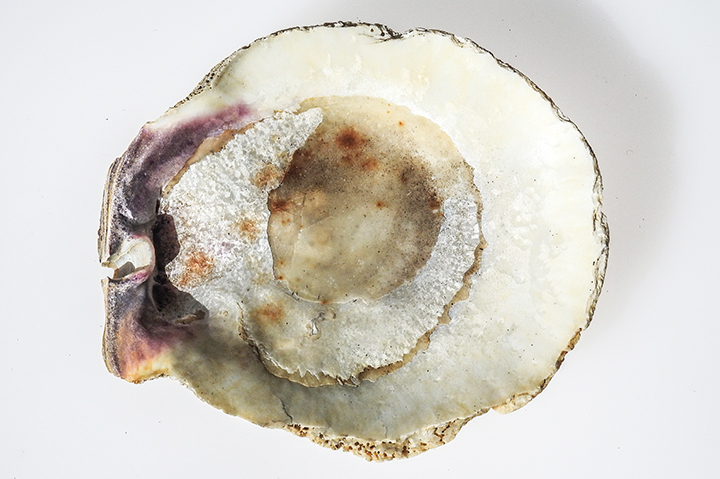

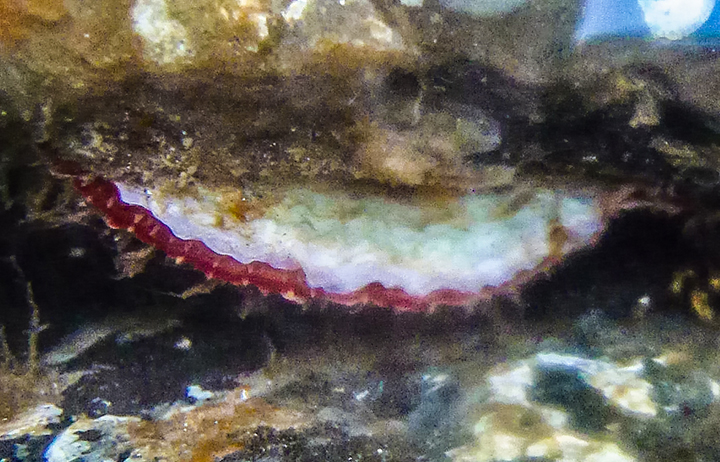

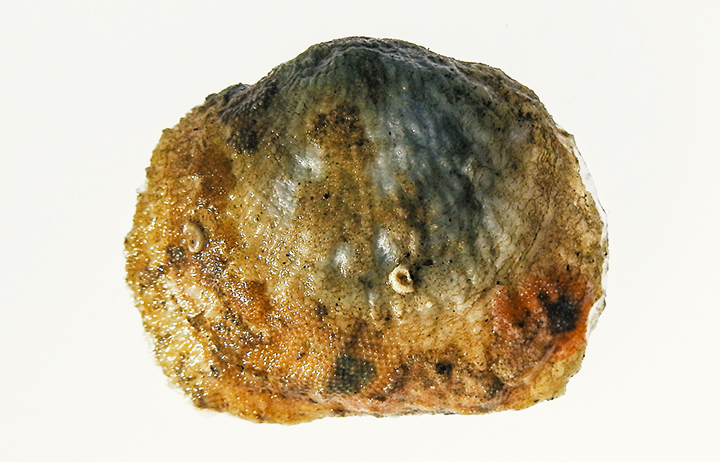

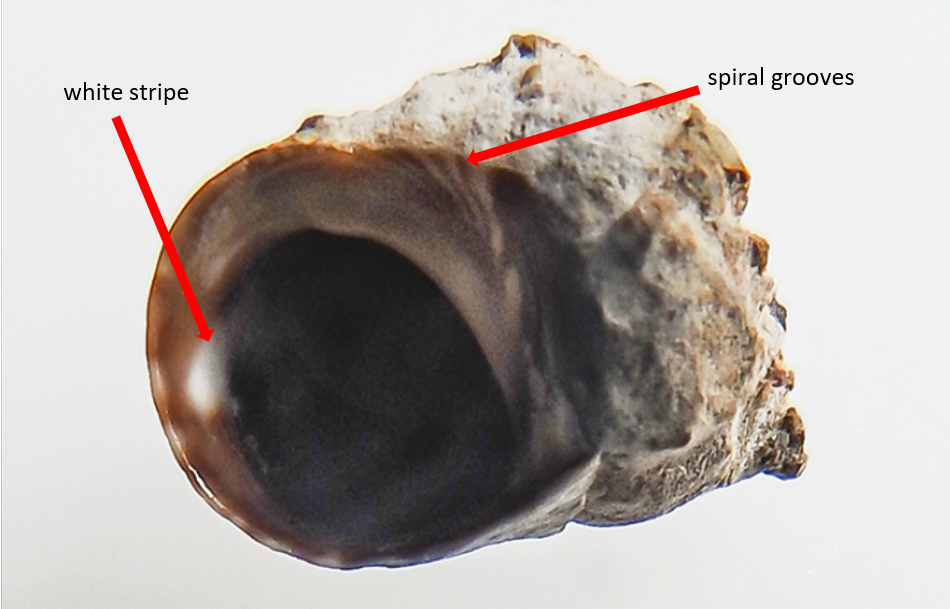

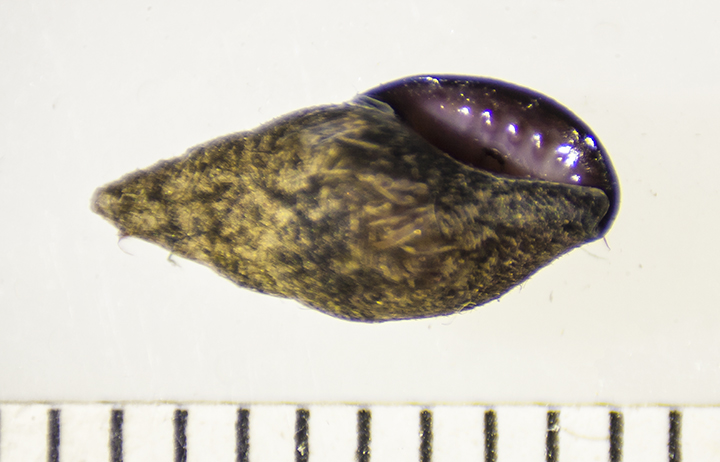

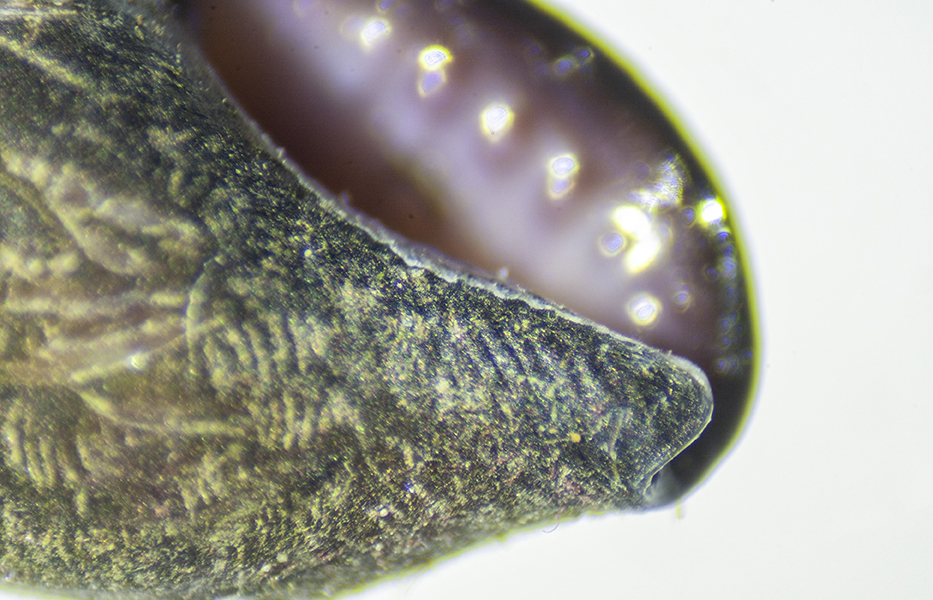

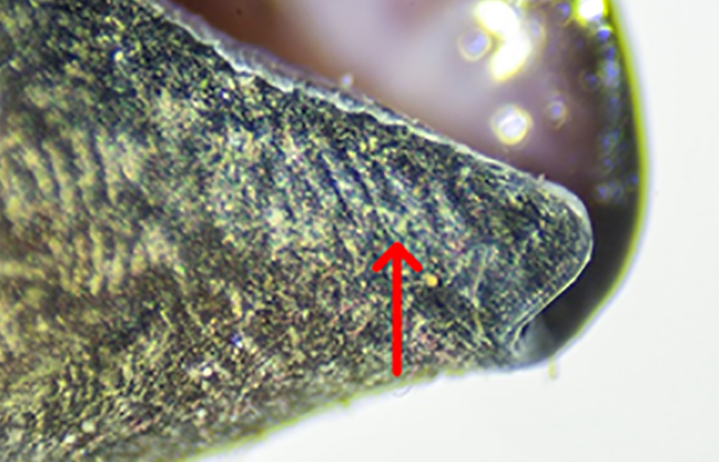

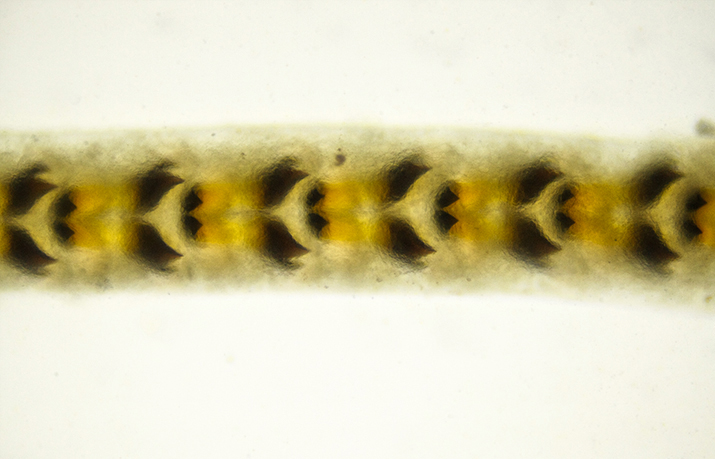

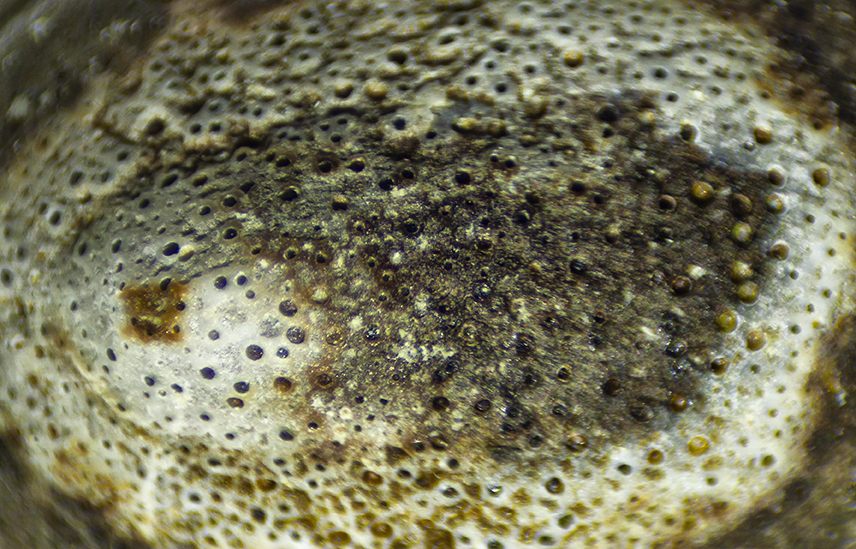

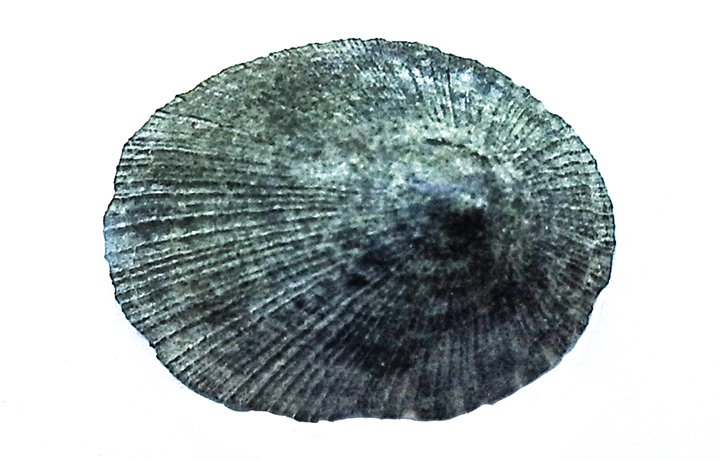

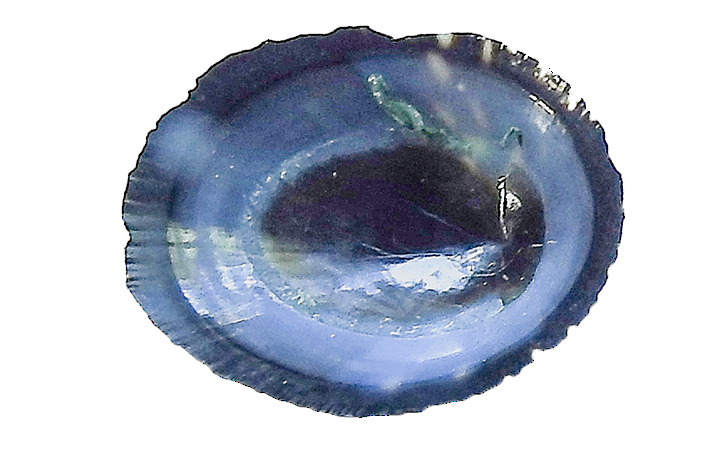

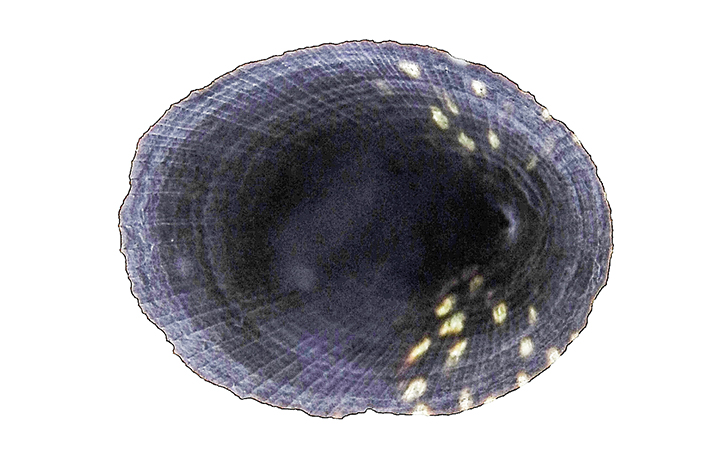

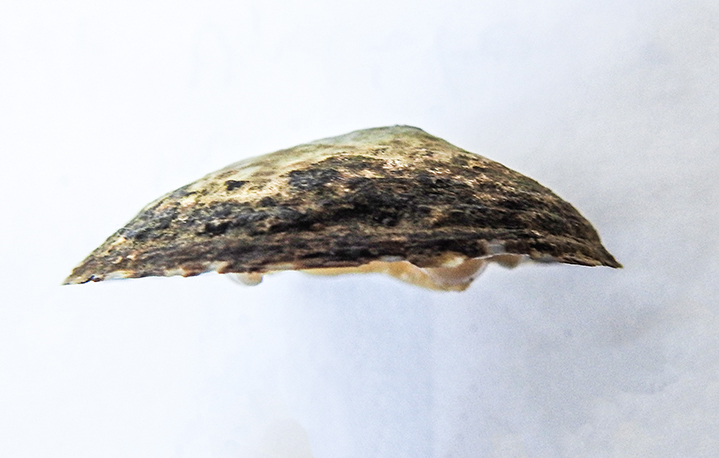

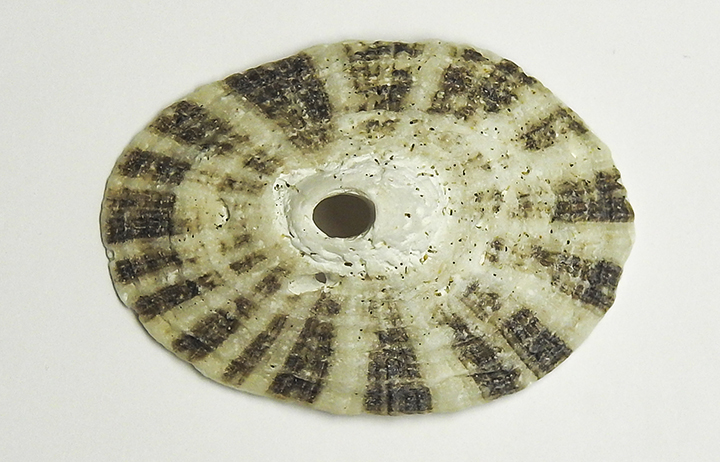

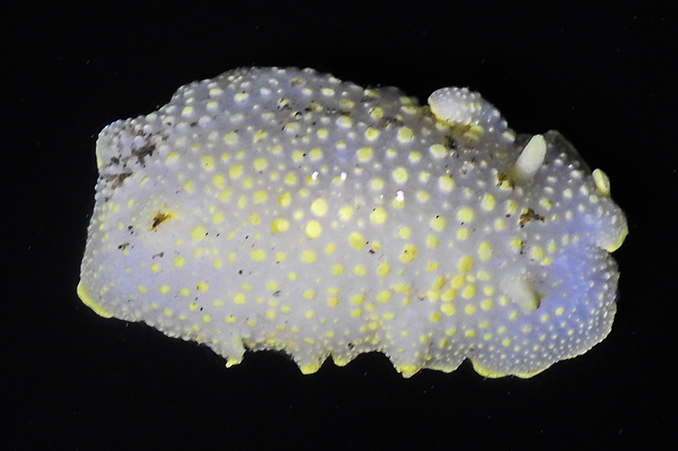

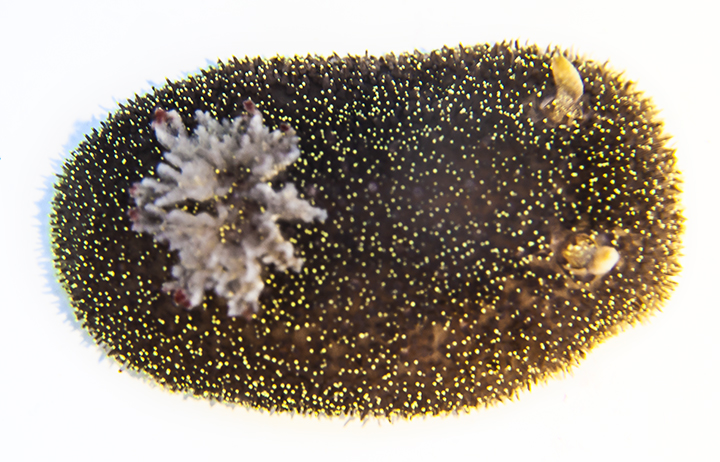

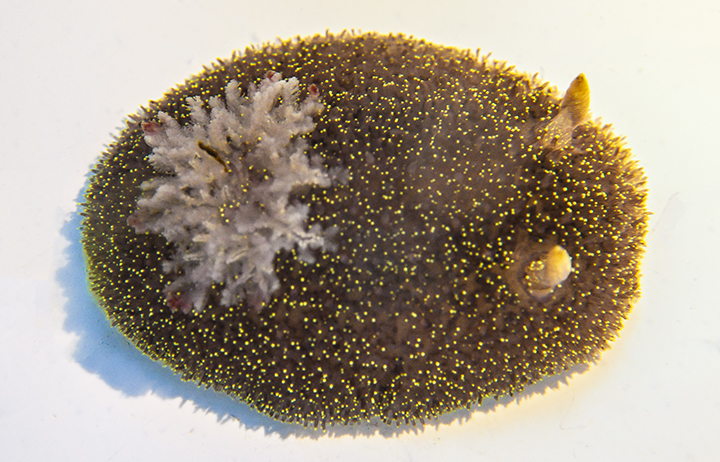

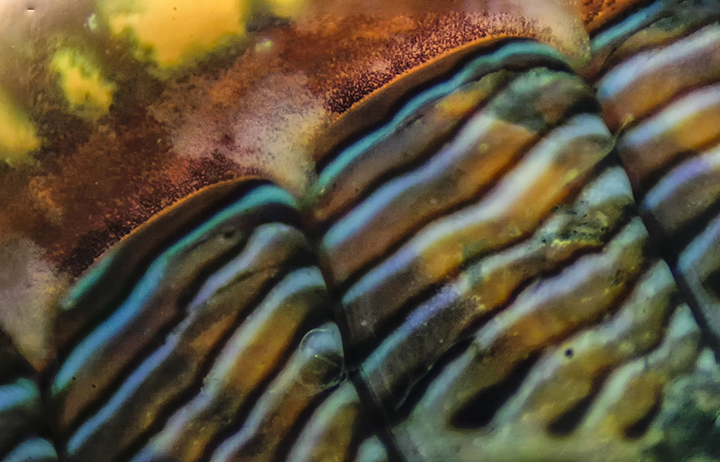

Nuttall's Cockle, because of its short neck, lives under just a few known as the heart cockle, basket cockle, and cockle clam, its species is named after Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859), an English biologist who spent a large part of his career exploring the America, including the Pacific Northwest, and whose name is associated with several clams. Its thick, rounded shells, up to four inches across and colored yellowish tan with brown or reddish accents, radiate 34 to 38 distinct ribs, crossed by fine growth rings. A strong burrower with a powerful, muscular foot, it can escape its major predator in the bay, the many-rayed sunflower star Pycnopodia helianthoides, by using its foot to almost leap away. Nuttall's cockle can live up to 16 years. Though tasty, it has a strong flavor and is mainly used in chowder and fettuccine. To open and shuck cockles easily, blanch them first in boiling water for about 20 seconds. You can find cockles in the sand and mud shallows on the east side of the bay.